The story by GREG FOX continues…

The Cult Of Bischof

Frank Bischof’s record as an investigator of major crimes enabled him to be considered one of the most effective detectives in Australian history. Today he is viewed as a black and white caricature of an older style of policing. For historians the former police chief represents an era in law enforcement in Queensland that would eventually be sullied by the admissions at the Fitzgerald Inquiry (being the “Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct”). Tony Fitzgerald QC recommendations would lead to the criminal convictions of numerous high-ranking police officers and three former government ministers.

Bischof knew of and promoted “The Joke”—an organised system of graft and corruption managed by dishonest police, involving payments from illegal gambling including starting price bookmakers as well as brothel and massage parlour operators. Decades later, disgraced Queensland Police Commissioner Terry Lewis would tell award‑winning journalist and true crime author Matthew Condon: “I never knew Bischof to be a grafter, a crook, a pants man. I knew him as a drinker and a racing man.” Not exactly a ringing endorsement of the former commissioner’s personal habits and character.

Ron Edington, the former Queensland Police Union President told the Fitzgerald Inquiry in 1988 that Bischof “had not been a corrupt commissioner but a ‘flamboyant’ man who liked to go to the races.”

The Big Fella

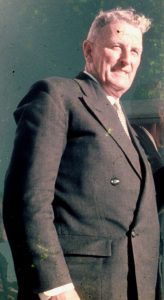

As a rising detective in the Queensland Police Force, Bischof was a copper to be reckoned with. Originally from the Darling Downs township of Gowrie Junction, Bischof was the fourth child of father, August Bischof, a dairy farmer, and mother, Sophia. After attending Toowoomba Grammar, he worked at a local cheese factory before joining the police service at 21. With his Protestant roots Bischof rose rapidly through the ranks, becoming a Sergeant in 1939 and by the late 1940’s was appointed Detective Inspector. Then in 1955 he earned the prized position as head of the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB). Boasting his truly impressive record as a crime-buster, Bischof was elevated to the commissionership on 30th of January 1958 by Premier Frank Nicklin of the Country Party. It was reported Bischof, a Freemason, beat out over 200 applicants for the position. Bischof was an imposing physical presence standing 6’2” and weighing over 16 stone. He displayed an air of worldly assurance and high sartorial standards. The “big fella” genuinely enjoyed the stature of being Queensland’s top cop and the many benefits that came with the position.

Bischof had no children of his own with wife Dorothy (a former dental assistant), whom he married in 1930. However, at age 53, Bischof was named Queensland’s first ever Father of the Year. The honour was in recognition of his commitment to the state’s youth and initiatives in mentoring wayward teenagers, and their parents. The door to his office was always open, particularly for his “Saturday morning clinic” for disadvantaged youngsters and at-risk youth. In 1963 he implemented the Juvenile Aid Bureau (JAB), with the then unremarkable Constable Terrence Lewis taking on the role as programs coordinator. The working brief of the new agency was ridiculed by some in the force and earned the name “the bum smackers”.

Condon in Three Crooked Kings, the first part of a definitive account of historical police corruption in state from the 1950s to 1980s, noted the bureau’s public relations promoted the childless Bischoff as the “father” to the state’s children. A man in-tune with young Queenslanders and the challenges of modern life. So was Bischof’s commitment to young persons the JAB was located next to the Commissioner’s office in Makerston Street, North Quay, in the city.

Ken Blanch, veteran The Courier Mail crime reporter suggested in his casebook The Taxi Driver Killer: The Southport Murder that Bischof had “a particular aversion to Southern criminals” and believed that they were responsible for most of the criminal activity in his sunshine state.

Source: ABC Online

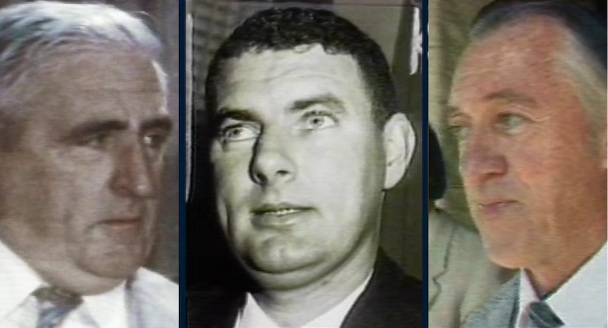

His Rat Pack

As the new Police Commissioner, the “big fella” cast a spell over many up-and-coming loyalists. And none were more significant than his “Rat Pack”—a term given to a trio of ambitious younger policemen: Anthony “Tony” Murphy, Glendon Hallahan and Terrence Lewis. Rumours had it they were his bagmen. This would spoken of again decades later at the Fitzgerald Inquiry. In return for their allegiance the “Rat Pack” would receive special favour. Tony Fitzgerald QC would state in his inquiry findings that “in some respects police corruption had acquired a quaint quasi-legitimacy the Bischof era”.

Following corruption allegations in parliament by Colin Bennett MLA, the State Member for South Brisbane on the 29th of October 1953, the activities of the upper echelon of police, including Bischoff, would be scrutinised. The Labor MP would speculate to the House “that the Commissioner (Bischof) and his colleagues who frequent the National Hotel, encouraging and condoning the call-girl service that operates there, would be better occupied in preventing such activities rather than tolerating them.” Bennett, a barrister by profession, planted the seed under parliamentary privilege … things were not as they appeared in Brisbane policing circles.

An inquiry into goings-on at the National Hotel was ordered by Premier Nicklin to commence in December 1963. The historic hotel, built in 1888 and located on the corner of Queen and Adelaide Streets at Petrie Bight, was the Commissioner’s preferred spot to socialise. A milieu of movers and shakers in the city, as well as in-house prostitutes frequented the popular haunt. Bischof was often spotted having long lunches, drinking at the lounge bar and in attendance at private parties on the first floor. An employee of the hotel, David Young soon came forward to tell his story. He told the Leader of the Opposition in state parliament that he had served Bischof free food and grog after hours.

Source: The Courier Mail

Incredibly, this Royal Commission headed by Justice Harry Talbot Gibbs, with its terms of reference narrowly looking back to the 9th of October 1958, found that there was no prostitution or call‑girl service operating at the hotel. After listening to 34 days of evidence (and more than 90 witnesses called) Gibbs went further in declaring that no member of the police force “encouraged, condoned or sanctioned” prostitution at the National Hotel. Also, nowhere within the 200-page report did it say that Bischof and his associates drank at the hotel after hours.

Five-time Walkley Award winning journalist Evan Whitton summed up the outcome of the Gibbs Inquiry in The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia’s Police State, lamenting to a degree: “It is supposed (then) that the result (of the Gibbs Inquiry) greatly emboldened the corrupt in the force.” This entrenched corruption inside the police force would continue uninterrupted through the 1960s and 1970s, into the 1980’s. Before it was eventually unveiled, in all its most sinister forms, to the Queensland public.

Hiley Takes Aim

Bischof’s personal and professional habits continued be scrutinised. Those within his inner circle knew he was a compulsive gambler. In the early 1960s, he was known to punt up to two thousand pounds at a single race meeting in Brisbane—a superfluous amount for that time. Soon after the Gibbs Inquiry, Bischof found himself embroiled in another unfolding and potentially career‑ending controversy. In this matter the usually supportive Country Party leadership started developing serious concerns about the Commissioner’s trustworthiness.

A cohort of illegal bookmakers from western Queensland had come to the capital to speak with then Minister For Racing and Treasurer, the Honourable Thomas Hiley of the Liberal Party. They had a tale to tell the Minister—and it was shocking. Police had, for a number of years, been extorting money to allow these country bookies to operate unencumbered. Worse than that, the Commissioner was positioned at the head of this conspiracy. Bookmakers alleged that half of the total money paid went to local police and the other half to Bischof in Brisbane. Payments ranged from 10,000 to 40,000 pounds on an annual basis per town depending on the size of the region the bookmaker would service. Payments to corrupt police totaled around 400,000 pounds with Bischof’s share making him quite wealthy. His regular cut was forwarded to Brisbane and laundered through legal bookmakers at weekly race meetings.

Hiley was keen to move on prosecuting the Commissioner, but the bookmakers and their associates refused to take part in giving evidence. Perhaps they were genuinely wary of the “big fella” and his connections or maybe they did not want the criminal activity to come to a complete halt. The Solicitor General thought the chance for a successful prosecution looked unlikely without direct corroboration. Nicklin was not willing to offer another inquiry either, based on the weight of the evidence available. The Premier did strongly admonish the Bischof. It’s claimed he told the Commissioner that if he did not sort out the issue with the western bookmakers and end these arrangements, then the enforcement of the law involving the racing industry and associated betting would be taken out of police portfolio altogether. The corrupt practices had to stop immediately.

Still, Hiley was adamant that Bischof resign, or at least be stood down on medical grounds. By 1967, Bischof endured several lengthy hospital stays. Suffering from chronic hypertension, years of work stress and excessive drinking had taken a physical toll. Hiley had the goods on the “big fella” but those around him lacked political will to make a move. Somehow Bischof held on but with his authority greatly diminished.

A Wig, A Mask & A Revolver

Late the following year, the Commissioner wisely made the decision to retire. The pressures and scrutiny of the top job became too much, as his mental capacities started to diminish alarmingly. Rumours of his psychological decline and paranoia were whispered in police corridors. The Premier ordered a medical evaluation of Bischof’s health. After taking extended holiday leave from the 14th of February 1969, he officially left the force in October, thereby allowing him to reach the age of official retirement. The “Big Fella” got to go out on his own terms, to a degree, after 44 years in the police force.

Source: The Courier Mail

The incoming commissioner Chief Inspector Norm Bauer, also a Mason, had pre-emptively commenced the transition of Bischof out of the top job. He was acutely aware the 64-year-old had become a liability to his fellow police officers and the government of the day. Bauer promptly ordered Bischof’s office cleaned out.

This occurrence became a peculiar anecdote provided by the indemnified Jack Herbert at the Fitzgerald Inquiry in September 1988. The notorious “Bagman”, a former Licensing Branch officer and one-time organiser of “The Joke” confirmed that in early 1969 he met with his associate, the formidable Detective Tony Murphy. Carrying a large suitcase, Murphy asked Herbert to store the item for safekeeping. The contents of the suitcase allegedly belonged to Bischof and had been found in an office clean-up by his driver Slim Somerville. Herbert looked inside the suitcase and found a wig, a paper mask and a revolver. He hid them under his house behind some fishtanks. Months later Murphy came back to retrieve the suitcase, and it was never spoken of again…

An Old And Very Sick Man

Five years later and well into retirement in the leafy western suburbs of Brisbane, Bischof was charged with shoplifting after attempting to steal from a city shop. This was an unforeseen fall from grace for the former chief of police. The pensioner had been living a low-key existence. Spending his time walking his dogs and tending to an already over-manicured garden at his modest home at The Gap. To stay occupied Bischof also sold Mater Prize Home raffle tickets for the hospital charity.

It was on Friday the 12th of July 1974 that Bischof was arrested for attempting to steal a couple of packs of cigarettes, a pouch of tobacco and other small items from Barry and Roberts department store. He was committed to stand trial for the theft of goods totaling $6.12. Fortunately for him, the prosecutor decided it was not in the public interest to proceed with the charges. His defence had presented a psychiatrist report stating that Bischof was an “old and very sick man.”

“Give Him An Operation”

Three months after the preliminary hearing, Halliday’s full trial in the Brisbane Criminal Court commenced. It was essentially a re-do of the committal. Halliday’s defence counsel, Mr W Elson-Green, told the jury that the case presented by the crown was “a purely circumstantial one.” The solicitor highlighted that no one had witnessed the crime and there was no way to prove that Halliday was on Currumbin Hill around the time the murder occurred. More importantly, no one had positively identified Halliday as even being in Southport on the day of the murder.

Mr Elson-Green reminded the court that no arrest in the McCowan murder had been made for more than a month. Until of course, a career criminal (his client) was in strife, laid up and seriously hurt (shot in the leg) in a Sydney hospital. Had Queensland Police found an easy mark for their taxi driver killing in the troubled Slim Halliday? The defence was adamant that all evidence indicated that his client’s “confession” had not been made to the investigators. Halliday was obviously a man that had been questioned many times by police on any number of matters over his adult life.

“Yet now it was suggested by police that he (Halliday) was blandly going to admit to having committed the worst crime (murder) on the calendar”, exclaimed Mr Elson- Green incredulously.

“Halliday was a hardened man who was used to dealing with police. A man like that would sooner hang himself than tell police the sort of things Halliday is alleged to have said out of the blue.”

Mr Elson-Green made a withering assault on the characters of Detectives Bischoff, Hocken and Windsor during the cross-examination of the prosecution witnesses. He proposed the police had verballed his client, attacked Halliday physically and encouraged him to commit suicide whilst in custody. During the particularly intense cross-examination of Detective Hocken, Mr Elson-Green asked the police officer about his interrogation of Halliday at their final interview at Sydney CIB. Hocken denied he told the accused:

“Listen c*nt, Bischof has been handling you with kid gloves. I think you ought to be treated differently. Now talk or we will bloody make you talk. Nobody would worry if we killed a bastard like you.”

Hocken would also need to rebuff accusations that Halliday was forcefully restrained to a desk by Sydney detectives and told they were going to give him “an operation”.

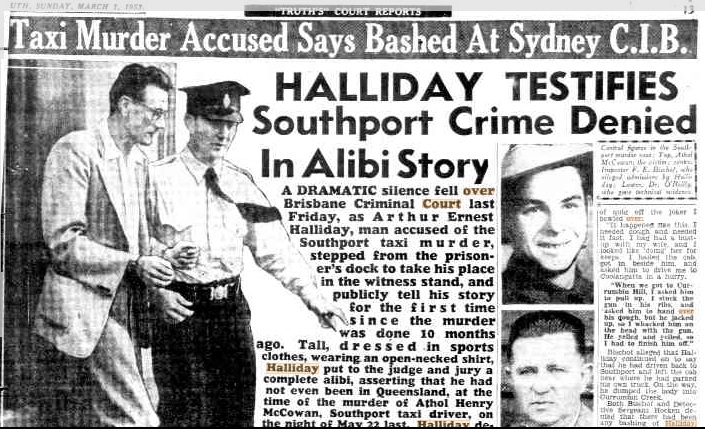

A Mythical Case

Halliday continued to make his own vigorous and sensational claims at the murder trial. Whilst on the stand being questioned by his barrister, he claimed that Detective Bischof told him in Sydney that he was going to “set him” for the murder of the Southport taxi driver. Asked by Justice Stanley what he (Halliday) understood this implied, Halliday said he thought that it meant that Bischoff was going to build a “mythical case” against him.

Source: The Truth (Brisbane)

Unsurprisingly the Crown Prosecutor, Mr Carter would run the counter argument to the defence, in his summation to the jury.

“The jury must decide whose evidence to believe. (Therefore) you must regard Halliday’s evidence (at this trial) as a fabrication from start to finish”, Mr Carter implored. He concluded by asking the jury whether they could believe that “Bischof was such a monstrous character that he would descend to the level of a conspiracy and weave a case against Halliday?”

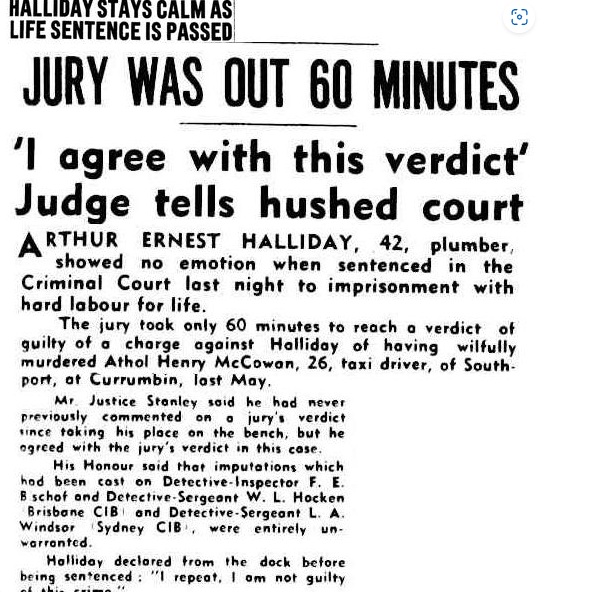

“I Am Not Guilty Of This Crime”

In the end it was the accused’s word against the reputation of the esteemed detectives. Arthur “Slim” Halliday was found guilty of having wilfully murdered Athol McCowan. The jury came to its finding after a 60-minute deliberation. The now convicted murderer showed little emotion as he was sentenced to life imprisonment with hard labour.

Asked by his Honour Justice Stanley if he had anything to say to the court, Halliday said, “I repeat, I am not guilty of this crime.”

Nonetheless his Honour seemed satisfied with the outcome. Justice Stanley’s final statements pushed back against the egregious accusations made under oath by Halliday. His Honour cited that the imputations cast on Detective Inspector Bischof, Detective Sergeant Hocken and Detective Sergeant Windsor were completely unwarranted.

Justice Stanley added that “when an accused made charges of wilful perjury against the police, (then) one of the jury’s privileges was to consider the character of the man that made those charges.” They surely did. Halliday was led away to the cells below the courthouse before being transferred to Boggo Road Gaol.

Source: The Courier Mail

Justice Denied?

Questions remain about records of convictions in cases where Bischof was the lead investigator and where he directly provided evidence and testimony to a court. Perhaps the Southport Taxi Driver Murder Case could be an outlier in Bischof’s infamous career – was the case run as a by the book homicide investigation – between Queensland and New South Wales police? One that secured a hard-earned conviction against a career criminal – and murderer. We will likely never know.

But it is clear his ties to a culture of corruption and illicit activities as the Commissioner from 1958 till 1969 bring the McCowan murder into the spotlight again. Halliday continued to assert till his death in 1987 that he was “verballed” by Bischof in the McCowan matter. He would later tell Brisbane Telegraph reporter Peter Hansen in 1979 that his murder conviction gave Bischof the credibility and the notoriety, to be named the Queensland Police Commissioner.

Halliday lamented, almost philosophically, after spending 24 years in prison for the McCowan killing: “Bischoff wasn’t a monster. He didn’t just pick anyone. He really thought I was right for the Southport murder”.

REFERENCES:

Arrest looming in Southport taxi man murder. (1952, 6 July). The Truth (Brisbane), p. 1. Trove (online).

Blanch, K. (2006). Slim Halliday – The taxi driver killer: The Southport murder. Jack Sim Publications.

Condon, M. (2013). Three crooked kings. University of Queensland Press.

Crowds throng through court for Halliday case hearing. (1952, 14 Dec). The Truth (Brisbane), p.36. Trove (online).

Detectives allegations: Halliday found he killed taxi driver for two quid. (1952, 10 Dec). Morning Bulletin, p.1. Trove (online).

Dickie, P. (1988). The road to Fitzgerald: Revelations of corruption spanning four decades. University of Queensland Press.

First day full report of Southport murder charge evidence. (1952, 10 Dec). The Courier Mail, p.3. Trove (online).

Found guilty of murder: Life for Halliday. (1953, 3 March). Townsville Daily Bulletin, p.1. Trove (online).

Francis Erich Frank Bischof (1904-1979). Australian Dictionary of Biography. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bischof-francis-erich-frank-9513

Halliday before court over McCowan death. (1953, 23 Feb). Brisbane Telegraph, p.1. Trove (online).

Halliday says police framed him. (1953, 5 March). Central Quensland Herald, p.22. Trove (online).

Halliday to face trial: 60,000 words by 47 witnesses in 7 days. (1952, 23 Dec). The Courier Mail, p.5. Trove (online).

Man charged on Qld taxi driver murder: Extradition order made. (1952, 13 Nov). Daily Mirror, p.4. Trove (online).

Only circumstantial: Claim on evidence by Halliday’s counsel. (1953, 2 Mar). Brisbane Telegraph, p.1. Trove (online).

Part of skull in court: Doctor gives evidence on McCowan injuries. (1952, 16 Dec). Brisbane Telegraph, p.1. Trove (online).

Pay respects to Athol McCowan: Big last tribute to taxi victim. (1952, 3 June). The Courier Mail, p.3. Trove (online).

Queensland ministers often sought favours. (1988, 2 Mar). Canberra Times, p.1. Trove (online).

Southport charge evidence: Tests with floats to check currents. (1952, 20 Dec). The Courier Mail, p.3. Trove (online)

Southport murder charge evidence – Full report: 2nd days hearing. (1952, 11 Dec). The Courier Mail, p.3. Trove (online)

Southport taxi driver murder: Inspectors evidence indicates confession. (1952, 10 Dec). South Coast Bulletin, p.13. Trove (online).

Taxi cab murder theories scrambled: Cribb Island drama starts new chase. (1952, 1 June). The Truth (Brisbane), p.3. Trove (online).

The Southport murder: Police appeal to residents. (1952, 16 July). South Coast Bulletin, p.3. Trove (online)

Whitton, E. (1989). The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia’s police state. ABC Enterprises.