By GREG FOX – True Crime Researcher & Essayist

“Corruption is a crime between consenting adults in private. The best remedy for it is to shine a light on it” – Phil Dickie: Author “The Road To Fitzgerald” – from ABC Conversations (Brisbane 612AM) 2009

The Gerald Edward (Tony) Fitzgerald QC led “Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct” stands as a momentous event in the history of the sunshine state. Fitzgerald’s written submission into these matters (officially titled Report of a Commission of Inquiry Pursuant to Orders in Council Dated – i. 26 May 1987; ii. 24 June 1987; iii. 25 August 1987; iv. 29 June 1989) is an extensive document. It’s not surprising given his probe, with its broad terms of reference, lasted two years (27 July 1987 – 3 July 1989) and heard from 339 witnesses. The report totals 638 pages. Much of it is an historical account, chronicling major occurrences in the political and policing landscape.

Tabled in Parliament in July 1989 by then Premier Mike Ahern of the National Party, its summary findings heralded a new era of accountability for many arms of the public service. Over 100 key recommendations were outlined by Fitzgerald. The most notable of his decrees related to criminal justice reform, separation of powers and electoral law adjustments. Importantly the report put forth a context for the generational and systemic corruption that existed within the police force and its networks in Queensland. Thirty-five years later the document continues to be reviewed not just by legal and governance academics but so too a younger generation of Queenslanders and organised crime aficionados (like yours truly).

In researching Frances Erich Bischof aka “The Big Fella” (and the Southport Taxi Driver Murder investigation from 1952) I begun to ask myself questions about the exact nature of said corruption within the Queensland Police Force. How long had this entrenched criminality actually been going on, what did it specifically involve and how large was its geographical reach? From what I can tell there’s no real definitive answer to this. What we do know is it was certainly endemic throughout the state. Influenced to a degree by cultural determinants of the time, socio-economic factors and limited institutional oversight. Generally speaking, a culture of taking money for the protection of illicit activities and giving favour existed. Fitzgerald sets the scene of the subtle graft in the immediate post-WW2 period in the “Evidence section” of his report:

“Corruption existed, but its spread and effect were restricted by the limited spoils available …”

“Patronage, rather than money, was the primary currency exchanged, although graft formed part of the picture.”

The features of this “patronage” are expanded upon in The Hillbilly Dictator: Australia’s Police State, Walkley Award winning writer Evan Whitton’s insightful look at Queensland – and its broken institutions. Whitton subtly describes those times for a copper working out west:

“The pay wasn’t good (for a policeman) , but ancillary emoluments were, particularly in the outback, where endemic corruption had an almost oriental dimension: the sergeant got his beef from the grazier, liquor from the publican, and his walking around money from the legal starting price bookmaker by way of the odds to a nominal five pounds on the winner in the last race in Melbourne…”.

Whitton adds:

“There are reports at election time the local inspector went around the illegal bookmakers in the area and mulcted additional sums for the Premiers Slush Fund”.

Fitzgerald expands on this malfeasance in his report and how it got a foothold within the force: The former federal court judge mentions the younger recruits that joined the police force into the 1940s and 1950s were exposed to many of these shady but accepted practices. Eventually more “conventional” corruption involving Starting Price (SP) bookmaking, illegal liquor sales, prohibited casinos and brothels became the norm by the 1960s. Those sworn to protect the community developed a “jaundiced view” of the institutions they were supposed to serve. Over time these junior police officers rose to senior positions inside the force and were remunerated to keep these arrangements in place. Deep distrust became the day-to-day mode of operating. Consequently, a dimmer of law enforcement developed in the wider community. And so it went…

“The Joke” looms large in this tale. Where did this “coded name” for the long-standing corruption within the police ranks originate? I could not find where expression was first referenced. It’s certainly coppers slang and was a term used by police almost cynically when in the presence of fellow members of “The Joke”. Fitzgerald gives these corrupt practices a timeline and distinction: the “First Joke” from 1959 till 1974. Followed by a period, I will name here, as the “Second Joke” (1976 – 1987), which commenced after Ray Whitrod, noted reformer and academic, resigned as Police Commissioner. Now here’s the thing about Queensland, a footnote to story if you will: Police ran organised crime in the sunshine state completely unencumbered. A specific distinction must be made. In the majority of organised crime scenarios, criminals operate the enterprise. In Queensland this was not the case. At the top of the criminal undertaking was the Commissioner – during the Frank Bischof and Terry Lewis eras anyway.

Fitzgerald specifically examined this culture and drew this telling conclusion:

“…in some respects, police corruption had acquired a quaint quasi-legitimacy by the Bischof era.”

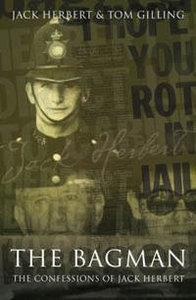

This is the backdrop in which Jack Reginald Herbert arrived at the Licensing Branch in 1959 as a plain clothes constable first class. “The Bagman” had joined the Queensland Police Service a decade earlier and solidified his uniformed credentials in Mackay and Brisbane. Prior he worked with Victoria police for 14 months on mobile patrols, after originally serving six months as a London bobby, back in his homeland. Licensing was a secretive cabal of cops located at the old police barracks on Petrie Terrace. Twenty or so officers were solely responsible for enforcing liquor and gaming laws across the city.

As an indemnified witness at the Fitzgerald Inquiry in September 1988, Jack then aged 63, allocuted about the first iteration of “The Joke” – and how he encountered it. A quick study, Jack soon realised that there “was something doing” within the branch. Most of his colleagues appeared to be living above their means. These men had plenty of money to drink, regularly socialise, drive expensive cars – and were well dressed. He also witnessed many known SP bookmakers receiving special treatment from these officers. Jack confirmed about half of the Licensing officers were part of a protection racket and receiving monthly payments. One of the notable officers already in on “The Joke” within the branch was future assistant commissioner Graeme Parker. The Licensing Branch in those days was true to its name, as Whitton outlines:

“The branch’s title was accurate. For a fee, some police licensed or franchised illegal gambling operations”.

In his autobiography The Bagman: Final Confessions of Jack Herbert, co-authored with Tom Gilling, Jack confirmed he and wife Peggy were living in a rented house at Carina with two infant children. They couple did not own a car and Jack walked along some distance along a dirt road before catching a tram to work. Jack offered a small glimpse into his motivations from the time:

“As a result of our financial predicament, I was ripe for the picking. That said, I won’t deny there was something in my character that was susceptible to corruption”.

“The Bagman” possessed a wonderful turn of phrase and could tell a yarn better than most. Born in Walworth in South London during the Depression, Jack could garner a laugh in even the most perilous of situations – and did so during the three weeks in the witness box at the inquiry in September 1988. The media and public gallery inside Court 29 of the Brisbane District Courthouse were enthralled. Daily newspaper sales skyrocketed in the capital. Fitzgerald summarised Herbert’s recruitment into this illegitimate world:

“He (Herbert) had not been in the Licensing Branch long when some colleagues told him he had been accepted into a group of men who were protecting SP bookmakers and that he could expect 20 pounds a month. Herbert’s salary was then about 90 pounds gross per month”.

During the 1960s the Licensing Branch protected approximately 40 to 50 SP bookmakers. Jack outlined that members of “The Joke” were responsible for their “own” SP bookmakers and the master list of those receiving protection were held by the “organiser”. Those participants in the scheme that did not have personal or direct contact with an SP were paid by the organiser out of monies collected from those members receiving more than their fair share. There was no central bank of corrupt funds at that time according to Jack. Of course, those members that played a bigger, more administrative role, in the corrupt system received a bigger payment.

By 1964 Jack was placed into the role as the “The Joke’s” organiser – a substantial promotion. Jack described he was “fastidious about keeping telephone numbers up to date and the bookies came to realise they could depend on me”. By 1964 each bookmaker was paying 20 pound a month to be in on the racket. Jack famously spoke about his abilities as to administer the scheme:

“I’m a pretty good organiser even if I may say it myself. Pommies are always fucking skites, I know that”.

Jack proffered that he was always on the lookout to recruit new members to join the scheme. He said that every single officer he approached to join “The First Joke” agreed to do so willingly”.

“I didn’t receive a single knock back.”

This highlighted Jack as some sort of “influencer at large” inside the criminal enterprise. “The Bagman” reminisced to The Courier Mail in 2002 outlining his method in assessing potential recruits:

“It was my job to check them (other police) out – see whether they were drinkers, liked a punt, had a mortgage”.

“Those in The Joke were the corrupt officers and the rest were the enemy.”

Eventually Jack started to deal directing with a good number of the SP Bookmakers himself. His earn as the bribe’s paymaster by the early 1970s was $800 a month – double his gross salary. In his autobiography he admits to the collection and distribution of bribe money for over a decade.

Circling back to the Southport Taxi Driver Murder Case I remain conflicted about the concept of “verballing” and how prevalent this unlawful behaviour was during these dark years. Would we ever know the likelihood of Arthur Ernest “Slim” Halliday being “verballed” (as he claims) by then Detective Inspector Bischof and his associates?

Perhaps definitive word on the matter of goes to Fitzgerald, from Pages 206-207 of his report – it carries a humorous anecdote by “The Bagman” – but nonetheless it’s a shocking indictment of the police. One that’s easily missed in the voluminous file, full of head scratching stories of police misconduct. Fitzgerald writes this, in an almost sarcastic tone, about the issue at hand:

“The verbal confession has long been a feature of Queensland criminal trials, with modifications and refinements over the last quarter of a century in order to boost its flagging appeal; for example, unsigned records of interview have been used to disguise the inherent improbability and proven defects of mere memory recall, and admissions to police have been supported by, or in some cases been replaced by, “confessions” by penitent criminals who have felt the need to share the burden on their consciences while awaiting trial to fellow prisoners who, improbably, have in turn felt obliged out of a sense of civic duty to pass on their information to police officers, often those with whom the confessors have some other relationship.”

Fitzgerald goes on:

“(Jack) Herbert said that although some police would not verbal, there was usually no need to sound out an unknown police officer to see whether he would give false evidence. It was just accepted. When a person was arrested police would sit down at the typewriter and “You would make the story up as you went along”.

“One of Herbert’s first verbals, according to his evidence, involved a man arrested for being in a public place for the purpose of betting. Herbert said they could not “quite” get the evidence on him. The decision was made to “drop one on him” or “brick” him. The story worked out involved evidence that, while they had been questioning the suspect, a person had approached him and said “give me 15 shillings each way on Harlequin,” to which according to the story, the suspect had said “Go away. You wouldn’t wake up if the town hall fell on you”. The charge against the suspect was dismissed, but the Full Court found in favour of the police on appeal, holding that the suspect’s statement about the town hall falling on his customer had been an admission.”

“Herbert told that he recalled quite well one of the judges saying by way of comment on the evidence of the reference to the town hall falling, “What brick by brick?” There is virtually no risk involved for police in misconduct such as verballing and the chances of success are excellent”.

“Ordinarily, any issue relating to disputed evidence involves a contest between an accused, whose credibility will usually be questionable and who most often will prefer not to enter the witness box, and police officers who support and corroborate each other. Even in blatant cases where lies have been exposed, action has seldom been taken against the police concerned….”.

And there it is – a stunning condemnation by Fitzgerald. One that goes to the MO of police undertaking general duties and making arrests pre-Fitzgerald. But were detectives prepared to “verbal” a suspect in a high-profile murder investigation – would the perceived reward to an individual police officer out-weigh the enormous risk? Would a man such as Frank Bischof, a Detective Inspector at the time, risk his career even if it meant maintaining his near perfect investigative record. And in the process sending a conceivably innocent person to gaol with a life sentence. Given what inquiry uncovered it appears in the realm of possibility…

To read POISONED JUSTICE: FRANK BISCHOF & THE SOUTHPORT TAXI DRIVER MURDER CASE